The Gang’s Getting Back Together

(Top, standing from left) Alan Ho, owner of Jade Dynasty Seafood Restaurant and Dada Spa, Salon and Cafe, and former Spencecliff employee; Kandi Miranda, entrepreneur and niece of former Spencecliff employee; Chantal Moearii Weaver, daughter of Spencecliff founder Spencer Weaver Jr.; Wendy Loh, entrepreneur and former Spencecliff employee; Shelly Seleni, entrepreneur and daughter of Spencecliff fire dancer Malo Seleni; and L&L Hawaiian Barbecue co-founder and former Spencecliff employee Eddie Flores Jr.; (seated from left) Kalo Mataele-Soukop, entrepreneur and former Spencecliff Polynesian dancer; and Norman Nam, Cinnamon’s Restaurant owner and former Spencecliff employee. PHOTO BY Anthony Consillio

An upcoming reunion pays homage to former Spencecliff restaurants’ employees and celebrates the bygone days of Hawai‘i.

Before he bought a restaurant for his mother and helped turn it into an L&L Hawaiian Barbecue empire that stretched across the islands and several states on the mainland, Eddie Flores Jr. was a busboy at the South Seas restaurant on Lagoon Drive.

He’d clear tables, make nice with the waiters — who’d split their tips with him — and have a meal with the kitchen staff.

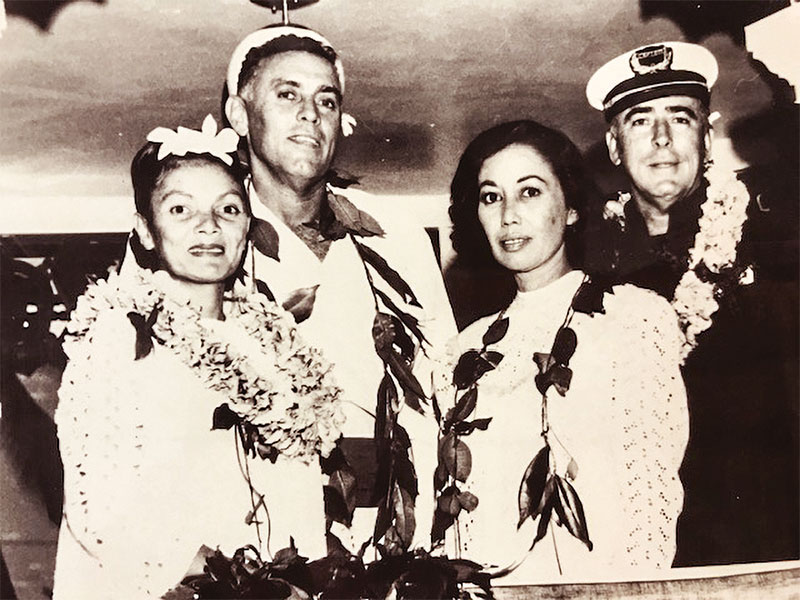

(Back row, from left) Clifton and Spencer Weaver Jr. with their wives (front row, from left) Daisy Weaver and Turere Tarome Tetahaimaui a Amo Weaver.

He’d never forget those staff meals because he grew up in Kalihi-Pālama, one of eight kids, and up to that point he’d never eaten so well.

In his recollection, it was around 1966 and South Seas was still brand new, decorated in the “tiki style” popular at the time — Polynesian prints, wood carvings and puka shell chandeliers.

Flores was just 20 years old and felt like he was stepping up in the world. His previous jobs had been washing dishes at University of Hawai‘i’s Hemingway Hall cafeteria and loading boxes at Dole Cannery.

Vintage art depicting the Ranch House in ‘Āina Haina IMAGE COURTESY CHANTEL MOEARII WEAVER

To his way of thinking, busboy was a high-class position, just one step below waiter, and he wasn’t just any busboy, he was a busboy at South Seas, a semi-fine dining establishment.

“The customers were nice, and the waiters and the management were nice,” he recalls. “Spencecliff was a really good organization because they really took care of their employees.”

Fisherman’s Wharf Restaurant before it was torn down in 2014. PHOTO COURTESY CHANTEL MOEARII WEAVER

To the younger generation, the name Spencecliff may not ring a bell, but for folks of a certain age it will evoke a flood of memories — of the treasure chests full of free toys for keiki diners at Fisherman’s Wharf in Honolulu and the Ranch House in ‘Āina Haina, of the hot coffee and pancakes at Coco’s on the corner of Kalākaua Avenue and Ala Moana Boulevard, or of the Polynesian revue at Hawaiian Hut next to Ala Moana Hotel.

“Every restaurant you can think of belonged to Spencecliff back in the old days,” Flores says. “I’m telling you, until 1985-86, they were an icon in the state.”

The Spencecliff restaurant empire began in 1939, when Spencer Weaver Jr. returned to O‘ahu after completing his service in the U.S. Navy. According to company literature, he’d first fallen in love with Hawai‘i as a youth in 1929, when his upper-class New York family took an around-the-world cruise that stopped in the islands.

When Spencer grew up, he became a Navy pilot and was stationed at Pearl Harbor in 1936. The assignment was short, but he found time to surf and join the Outrigger Canoe Club.

He finished his military service on the mainland but returned to Hawai‘i with no concrete plans. After a tepid foray into real estate, he ordered six eye-catching Swanky Franky hot dog carts and set up shop at the corner of Ala Moana Boulevard and Ena Road.

Swanky Franky had been popular at Floyd Bennet Airfield in New York and the entrepreneurial Spencer took a gamble that they’d be a hit in Hawai‘i as well.

When his younger brother, Clifton, arrived on vacation from the Virginia Military Institute in 1940, Spencer convinced him to stay and join the business.

After the hot dog carts came a coffee shop, then a bakery and then a request from the U.S. Army for Spencecliff to run the post exchange, restaurant and beer garden. Eventually, the brothers’ corporation would grow to more than 50 restaurants that employed thousands of islanders and fed even more over the course of nearly five decades. It also included two hotels in Tahiti.

When the Weavers sold the company in 1986, it felt like the end of an era. Although some former Spencecliff restaurants carried on under new management or endured in different iterations — Fisherman’s Wharf hung on until 2008 and bulldozers tore it down in 2014; a shell of the South Seas remains as part of the Aloha Kia dealership near Daniel K. Inouye International Airport — it was never the same. And all these years later a nostalgia for the Spencecliff days lives on among those who remember.

“I really truly believe it boils down to caring,” says Chantal Moearii Weaver, Spencer’s daughter, about why her family’s restaurants seem to have captured the zeitgeist of the times. “My father cared so much about his employees, and, of course, so did my Uncle Cliff.

“Their philosophy was if you take care of them, they’ll take care of you and I think that’s what happened. The employees were very passionate about what they were doing. They embodied that in the customer service, which was not only taking care of the customer but of their coworkers as well.”

Moearii Weaver grew up during the golden days of Spencecliff, when entertainer Hilo Hattie would perform at Queen’s Surf while handsome young men climbed coconut trees to shower the audience with plumeria lei.

“It was like you were in someone’s backyard,” she says, describing mats on the lawn for seating and whole pigs roasting in an imu.

She also recalls stories about how waitstaff would greet regular customers by name, seat them at their preferred table and have the kitchen prepare their favorite meal before they even ordered.

“My father was all about customer service,” she says. “He wanted to please the customer because if you don’t, how many people would talk bad about the restaurant, right?”

She says her father and uncle treated employees the way they wanted employees to treat customers. One memorable example — the company kept a record of their employees’ birthdays and sent them a small cake to mark the occasion.

Moearii Weaver believes if her father and uncle were still alive, they would want to do something special for their former employees. So later this month, she’s hosting a Spencecliff Employees Reunion at Ke‘ehi Lagoon Memorial.

Melveen Leed, who performed at Spencecliff restaurants back in the day, has agreed to sing at the gathering and Moearii Weaver is hoping to serve Tahitian Lanai’s famous banana muffins — one of Spencecliff chef Anderson Washington’s most popular desserts.

Mostly, though, she wants to spend time with folks who may remember preparing those muffins at the restaurant.

“I just want them to reconnect with each other and be able to share their stories,” she says. “Because a lot of them, when they share, they share from the heart.”

This year’s occasion will be the second Spencecliff Employees Reunion. The first took place back in 2008 at the Hawaiian Hut, which at the time was owned by former Spencecliff vice president Gordon Yoshida. About 300 people attended.

The Hawaiian Hut closed for good shortly after that gathering, but for years, Kalo Mataele-Soukop had ruled the stage there as director and producer of the Polynesian revue. Her dance troupe would put on two shows a night in front of packed crowds.

Mataele-Soukop met her late husband, a pilot from Canada, while dancing there and their lengthy courtship included many brunches at the Tahitian Lanai.

When the pair tied the knot in 1975, the wedding was probably the largest the state had seen. More than 4,000 guests packed the Neal S. Blaisdell Center to watch.

“Almost all of them from Spencecliff came,” Mataele-Soukop says. “Except for those who had to work, they all came.”

She would go on to be the first woman and first Polynesian to serve on Polynesian Cultural Center’s board of directors.

Mataele-Soukop and Flores are not the only entrepreneurs who got their starts at Spencecliff. Victor Lim, owner of several McDonald’s franchises on O‘ahu, spent nearly two years at the Beer and Grog in Waikīkī. Norman Nam, owner of

Cinnamon’s Restaurant in Kailua, managed several Spencecliff restaurants in his younger days. And Alan Ho, owner of Jade Dynasty Seafood Restaurant in Ala Moana Center and Dada Spa, Salon and Café in Ala Moana Honolulu by Mantra, paid for college by working as a busboy and waiter in Spencecliff eateries, then joined its management training program.

“Each (Spencecliff restaurant) was a different unit and unique,” Ho says. “So I picked up a lot of different management skills, how to deal with people, how to do food cost control and everything else.

“So many people in the food industry came from Spencecliff … so you have to give credit to Spencer Weaver. He started with a hot dog stand and became very successful.”

Some may argue that success continues today, even though the restaurants are no more.

Says Chantal, “While the restaurants were bought out and dissolved, the legacy of Spencecliff continues in the people we invested in.”

Spencecliff Employees Reunion

10 a.m. Sept. 24

Ke‘ehi Lagoon Memorial

$40 per person

(Venmo @Chantal-Weaver or make checks payable to Chantal Weaver)

BYOB

To RSVP

Call Chantal Moearii Weaver at 808-277-5358 or email hwnrealestate@gmail.com