Tough Enough

Before she grew into a confident, battle-tested coach who helps others conquer their stress demons, Debra Lewis was a fresh-faced cadet fighting to overcome her own anxieties.

On her second day at West Point, Lewis “about had a coronary” after realizing she had to complete a 2-mile run. To her dismay, the mettle-testing exercise was to be performed over hilly terrain while she and her classmates ran in formation, with planned drills sprinkled in along the path to further exhaust the participants’ muscles.

Despite her background as a strong swimmer and competitive horse rider, Lewis understood her body well enough to know she probably would not make it. In her mind, she was almost sure she’d upchuck her last meal at the one-and-a-half-mile marker — if she even got that far. Moreover, as part of the first group of women allowed to enter the prestigious military academy in 1976, she and others faced both internal and external pressure to prove they could serve their country well alongside men.

In Iraq, Col. Debra Lewis hands a bag of soccer balls to the headmistress of an all-girls school, which Lewis and her team built. PHOTO COURTESY DEBRA LEWIS

Suffice to say, the increasing palpitations in her chest and the growing consternation in her head were very, very real.

“When we first started out on the run, I had two other women in my formation,” recalls Lewis. “The first woman fell out within the first half mile — and my heart started going crazy!”

On the brink of bowing out of the run herself, Lewis happened to glance over at the unit’s only other remaining female. To her surprise, the cadet was a picture of serenity. She even wore a smile as she easily kept pace with the men.

Emboldened by her classmate’s calm visage, a now determined Lewis made a pact with herself as she silently ordered her lungs to expand and contract, and her legs to keep moving along the path.

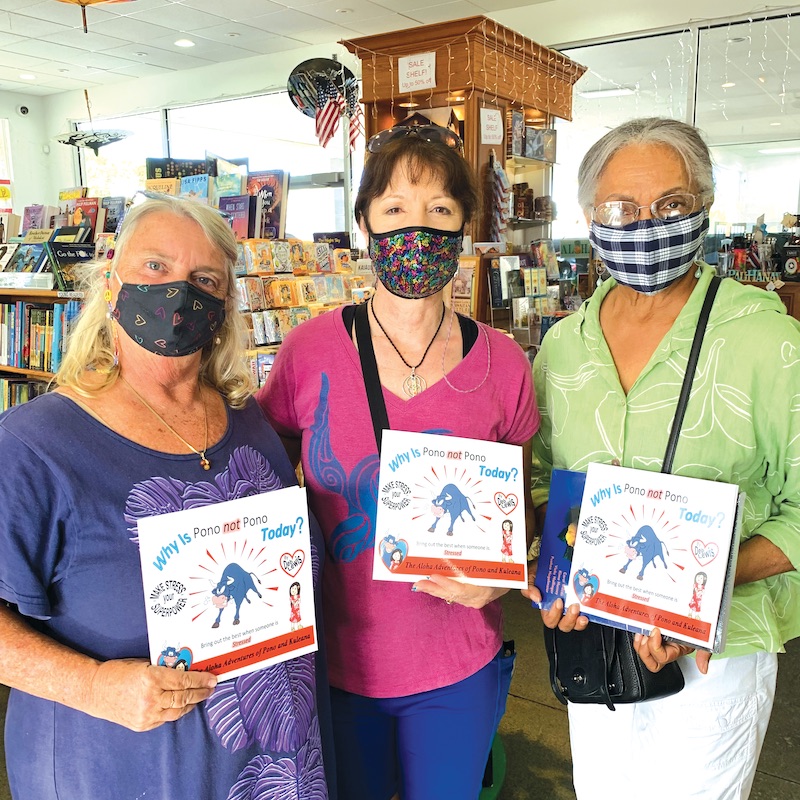

Fans of Lewis (center) and her just-released book include (from left) Christine Reed, co-owner of Basically Books and Petroglyph Press in Hilo, and Dr. Sonia Juvik, professor emerita at University of Hawai‘i at Hilo.

“I said to myself, ‘I’m going to pass out before I fall out,’” she remembers.

Lewis neither fainted nor threw up that day. In fact, she not only completed that run but every run thereafter. In figuring out how to control her breath and heartbeat, she discovered she could do extraordinary things when she allowed her mind to overcome a daunting challenge.

As she explains, “I learned that stress can be your superpower if you harness it, tame it and focus on what you want done.”

Little wonder why Lewis — a retired U.S. Army colonel who just released her book Why is Pono not Pono Today? — is one of the world’s foremost coaches on stress management.

While Debra Lewis followed in an RV, husband Douglass Adams traversed the entire continental U.S. in 2011 before completing the couple’s yearlong “Duty, Honor, America Tour,” on the Big Island. That’s where the couple ultimately settled. PHOTO COURTESY DEBRA LEWIS

“We need to be stronger,” demands the Hilo resident. “We must figure out a way to handle more stress so that when we face challenges, we can bring out the best in everyone and get more done.”

Her book captures the essence of her Mentally Tough Women initiative, which seeks to strengthen both women and “enlightened men — or those unafraid of strong women at their best” — through online courses and one-on-one sessions.

Two of her free courses on extreme stress and stress basics have already registered 3,800 people from 110 countries, she says.

“When I retired (in 2010), I wanted to help people be successful when things got tough,” adds Lewis, whose book may be purchased at mentallytoughwomen.com. “It took a while to come up with Mentally Tough Women, but the idea was how do we gracefully handle tough situations? People keep telling us to de-stress. The problem with that is, are problems getting easier or are they getting tougher? Are people dealing with it well or dealing with it badly?”

In many ways, Lewis’ three-decades-long career in the military — which includes surviving life downrange in Iraq as well as in Washington, D.C., during the 9/11 attack at the Pentagon — makes her the ideal mentor and motivator for those hoping to overcome obstacles and reach their potential.

“I’ve faced death,” she states. “I’ve faced people trying to bomb me, shoot me, kidnap me, insult me and put me down. I’ve had it all. I was asked a question recently, ‘How do you handle (stress)? Well, I said, for one, you learn to get back up. And in my case, I’m going to get back up fast! I’m never going to wallow in it.”

It only seems natural that Lewis would wind up in the military. Her father, Bennett, graduated from West Point and was a mechanic in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II. He also served in multiple wars before retiring as a lieutenant general in 1984. Even her mother, Malvene, had ties to the military as the daughter of a naval officer.

Still, Lewis — who was born in Frankfurt, Germany, and raised in locations around the world — claims her career pathway was anything but a foregone conclusion.

“I was going to be a doctor,” admits the woman who planned on attending the University of Virginia following high school graduation.

Circumstance, however, would pull her in another direction after a cadet friend of an acquaintance asked the young woman with a clear passion for horses, “Have you thought about going to West Point? I can get you on the riding team.”

Intrigued by the offer, Lewis simply replied, “OK.”

“My mother was the rider in the family, so I got that from her,” says Lewis, whose father taught her and her two older brothers to swim at an early age.

“As a young person, you want to do things tough early on. I think that’s where I get a lot of my toughness. It was tough being a horseback rider,” she continues, adding that she ultimately became captain of the equestrian team during her senior year at the academy.

“It was also tough being a swimmer and moving around a lot. I think my path could have taken me in a number of ways, but I was definitely drawn to West Point.”

Lewis is certainly proud of being a part of the first graduating class of 62 female cadets. In the years since, the U.S. Military Academy has seen more than 5,000 women successfully pass through its hallowed halls, and today, its female population comprises 25% of the corps.

Attitudes about the sexes have certainly changed in the last four decades, she acknowledges.

“They didn’t think we could compete back then. They would say (to male cadets), ‘How could you possibly let women graduate from West Point?!’ My own classmates stopped talking to me at times during my four years because they were getting hazed and they didn’t want to take the abuse. But I was like, ‘Join the club, be part of the group! It’s not so bad — you’ll get used to it!’” she says with a laugh.

Lewis continues: “West Point was a huge test. I knew it would be hard and I thought I’d be prepared, but no one can prepare you for a social revolution. There was a firestorm of publicity and controversy with people weighing in on both sides, and the faculty and cadets were all whipped up. Even the superintendent before we arrived said, ‘Over my dead body will women come to the academy.’ And that created a very rough environment.

“But it was good for me because if you can survive in that environment and learn to still be yourself, then that can be very helpful.”

Lewis survived and then some. Following her time at the academy, she also learned to manage large projects while training and supervising scores of people.

After joining the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, she was put in charge of two districts: first in Philadelphia, where she oversaw 550 employees across five eastern states; and second in Seattle, where she managed 850 people scattered over four western states.

Later, while assigned to the Pentagon, she was the engineer in charge of writing regulations that would protect the highest levels of the military from terrorist attacks. Ironically, she was there at the U.S. Department of Defense headquarters the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, when a hijacked commercial airliner crashed into the western side of the building.

“I’m always where trouble is,” she says jokingly.

Five years later, she was asked to deploy in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom and take command of the Gulf Region Division District. There in the western Asian theater, she was asked to provide engineering and construction management in Baghdad and Al Anbar Province.

Despite the constant bombings all around, the hijacking of many of her crew’s supplies and the heavy loss of life (including many of her own Iraqi contractors), the experience was incredibly rewarding, she notes.

“My time there allowed me to do the most phenomenal engineering work that I’ve done in my career. We had a $2.1 billion construction program. We built everything from fire stations and treatment plants, to power stations, court houses, roads and schools,” explains Lewis. “You name it, we were building it in trying to give the people of Iraq infrastructure.”

Lewis and husband Douglass Adams (also a West Point classmate whom she wouldn’t meet until 17 years after they graduated) moved to the Big Island in 2011. Their arrival marked the culmination of the couple’s yearlong “Duty, Honor, America Tour,” in which Adams rode his bicycle over 18,000 miles, crisscrossing every state while saluting veterans, active duty personnel and their families as his wife followed him in a rented RV.

After touching down in the islands, the equally tough Adams biked the remaining 222 miles on the last day of the tour and, along with Lewis, decided the 50th State would be where they’d plant their roots.

For Lewis, Hawai‘i has been “the longest I’ve lived anywhere in one place in my life.”

“It was fate,” concludes the woman who earlier in her career was briefly stationed at Schofield Barracks and Fort Shafter on O‘ahu. “Along the way as we crossed the entire country, we kept asking ourselves where the ideal place to live would be. I can only say that it felt like coming home when we got to the islands. They really spoke to us, especially the Hilo side of the Big Island.

“With all the hardships and things we’ve experienced in our lives, it was the place to come and be welcomed. I think it was meant for us.”