What’s In A Name?

‘Imiloa Astronomy Center and its executive director Ka‘iu Kimura have launched a far-out pilot program that weaves Hawaiian culture into the naming of astronomical objects.

A little more than a year ago, Ka‘iu Kimura, executive director of ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center in Hilo, got a call from Doug Simons, director of the Canada-France-Hawai‘i telescope atop Mauna Kea. He said, “Ka‘iu, we’ve got a hot object coming through our solar system. I can’t give you much detail, but I’ll give you 72 hours to come up with a name.”

“This was a ‘not-even-once-in-a-lifetime occurrence,” says Kimura, who has led ‘Imiloa since it was built 13 years ago. “This thing came from deep space through our solar system and left. It was completely unique and weird!”

So, Kimura called the only man she could think of for the job — the man who is her inspiration for becoming fluent in the Hawaiian language — her Uncle Larry. Larry Kimura is a professor at UH-Hilo’s College of Hawaiian Language, the man recognized as the grandfather of the Hawaiian language revitalization movement and part of the team that developed Hawaiian content at ‘Imiloa.

Within 48 hours, Uncle Larry came back with a name: “‘Oumuamua” (pronounced oh-moo-ah-moo-ah) which means: “first scout or messenger who has come from a distant place.”

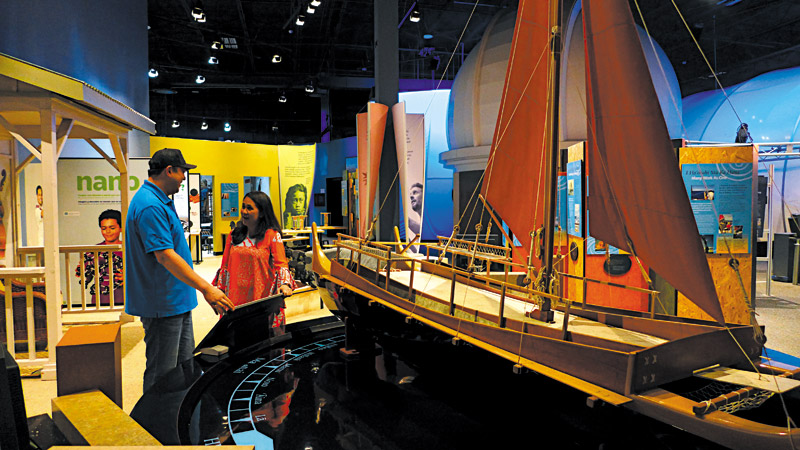

Imiloa Astronomy Center executive director Ka‘iu Kimura and guest services associate Kamaka Wakita talk story in front of the center’s Hōkūle‘a exhibit. KATIE YOUNG YAMANAKA PHOTOS

“We put it back out into the science community, and they loved the meaning — here was this scout or messenger that came to our solar system to check us out,” Ka‘iu Kimura recalls, noting another contender was the name Rama — short and easy to pronounce — inspired by the 1983 science fiction novel Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke. “But before the (International Astronomical Union) could officially name it, our Hawaiian name went viral. All the media outlets picked it up, and people were calling asking to record me saying the name so they could pronounce it correctly.”

‘Oumuamua, which is an odd cigar-shaped asteroid, is the first confirmed object from another star to visit our solar system. First spotted by the Pan-STARRS telescope at Haleakalā Observatory, it was theorized that such objects were out there, but this was the first proof of their existence.

“It spun into this huge international frenzy,” Kimura says. “We didn’t realize the impact it was going to have on the scientific community.”

Ironically, the discovery of ‘Oumuamua came in the midst of a project that Kimura and others were planning at ‘Imiloa to further their mission of connecting the cultural traditions of Hawaiians with modern-day science.

“We took the response to naming ‘Oumuamua as a sign that this new project was going to be significant,” she says.

The pilot program for A Hua He Inoa — He Noi‘i Nowelo i ka ‘Ike Ku‘una Hawai‘i o ka ‘Onaeao — involving Hawaiian-speaking high school students from Hawai‘i Island and Maui, took place last year. Led by ‘Imiloa in conjunction with Maunakea Observatories and the UH-Hilo College of Hawaiian Language, it is designed to position Hawai‘i as the first place in the world to weave traditional indigenous practices into the process of officially naming astronomical discoveries.

Keiki can enjoy myriad activities at ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center, including getting hands-on experience with Moanahoku Hall’s exhibits.

“The program takes a look at these objects and how they relate to the stories of origin that have been passed down over the generations,” Kimura explains. “These observatories allow us to connect to our ancestors in a different way. But it all starts from our traditional knowledge.”

In the future, Kimura says they hope to include students of all ages so they can gain direct access to new discoveries and understand the science behind them while building their knowledge of Hawaiian language, history and naming traditions.

“This program creates pathways in which language and culture are at the core of modern scientific practices,” explains Kimura. “We recognize that people around the world connect with the skies and have their own protocols and traditions for naming objects. We want to encourage more of that to happen. For our program, we are focused on the discoveries made with our telescopes on Haleakalā and Mauna Kea. Those are the instruments that allowed these objects to first be seen on Earth. We thought this naming program would be an excellent way of honoring Hawai‘i’s indigenous culture.”

Last year’s pilot culminated in the selection of two Hawaiian names for two major astronomical discoveries: “Kamo‘oalewa,” meaning “fragment orbiting in the heavens,” for an asteroid that is orbiting our sun, and “Ka‘epaoka‘awela,” meaning “the mischievous or strange one,” for an asteroid near the orbit of Jupiter that moves in an opposite or “retrograde” direction. These two names have been proposed to the International Astronomical Union, which governs observatories and astronomical science worldwide.

Pounding kalo

“These students made history with our pilot program — learning that their voices are not only important, but necessary,” Kimura says. “They were part of something that showed them how we can use the traditions that built us to continue to carry us forward.”

Kimura’s cultural heritage, life experiences and educational background have helped her guide ‘Imiloa’s programs. A graduate of Kamehameha Schools Kapālama, Kimura earned her bachelor’s in Hawaiian studies at UH-Hilo, and her master’s in Hawaiian language and literature. She was also selected as a member of the Hōkūle‘a long-distance voyaging canoe team as part of the crew that sailed from Okinawa to Japan in 2007 for the voyage “One Ocean, One People.”

Kimura was in graduate school when talks started about building ‘Imiloa, a world-class 40,000-square-foot exhibition and planetarium complex located on nine acres in the University of Hawai‘i’s Science and Technology Park. It was developed by a team of educators, scientists and community leaders who felt there was a need for a facility showcasing the connections between the traditions of Hawaiian culture and the groundbreaking astronomical research conducted at the summit of Mauna Kea.

“When the opportunity came up to work on this project that was going to bring these two world views together in one house that the community would share, I was honestly a little conflicted. I knew people that I cared for had strong opinions about astronomy on Mauna Kea,” she recalls. “But people like my Uncle Larry were very committed to participating because we needed to have people contribute who had those cultural and familial ties to Mauna Kea. For me, it became the responsibility of representing these connections so the center could truly reflect a Hawaiian connection to the mountain.”

‘Imiloa’s bilingual exhibit has labels in Hawaiian first, then English. “It reconnects the Hawaiian identity to a science of its origins,” explains Larry. “I believe more contributions can occur through Hawai‘i’s unique offerings in science. It’s not easy to keep an education center such as ‘Imiloa operational from its establishment 13 years ago. Ka‘iu understands the importance of where she comes from as a special gift for living in the wider world.”

Sharing the story of ‘Imiloa’s success is a lesson for other communities as well, says Kimura.

“Understanding Hawaiian perspective is necessary, and we’re seeing a lot more growth in this area,” she adds. “When we were building ‘Imiloa, there weren’t a lot of science centers or museums founded with this idea of indigenous knowledge and modern scientific knowledge coming together.”

Those who built ‘Imiloa wondered: How do you create an environment where both indigenous communities and modern scientific communities feel comfortable coming together?

“Embedded in our language is the way we think and relate to each other and to our environment around us,” Kimura says. “Language is code for how we view our world, and I think there is a keen interest now to better understand that world view — to better understand the Hawaiian way of thinking — and connecting to people and place and to new discoveries.

“Now, 13 years later, we’ve realized that although everyone may have a personal opinion regarding the issues surrounding Mauna Kea, everyone is 100 percent supportive of providing our local keiki and the community with educational opportunities. It’s important to keep ‘Imiloa a place of learning and a place of safe dialog. Our job is to be a conduit to the university and the institutions conducting research, and to provide community access to those discoveries. There are some truly amazing things happening here.”

‘Imiloa Turns 13

‘Imiloa will celebrate its 13th birthday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Sunday (Feb. 24) at the center. This year’s festivities, sponsored by KTA Super Stores, offers free admission for the whole family to explore exhibits and other hands-on activities that will bring this year’s theme, “aviation,” to life.

Demonstrations from various aviation professionals, flight simulations, make-and-take stations, full-dome presentations on aeronautics-related topics, drone-fl ying demos, and a scavenger hunt will take center stage, thanks to partnerships with organizations such as Maunakea Observatories, Civil Air Patrol, STARBASE Hawai‘i, UH-Hilo and Hawaiian Airlines.

“Every year, this celebration is an opportunity for ‘Imiloa to thank the community for its support,” says executive director Ka‘iu Kimura. “We chose aviation this year in anticipation of UH-Hilo’s proposed bachelor’s degree in aeronautical science, and because of all the opportunities that aviation and aeronautics present. It’s not just the opportunity to fly places anymore. Aviation is also being used in astronomical research right here on this island to help us understand our world.”

More than 2,000 guests attend ‘Imiloa’s birthday p˛‘ina every year, including awestruck keiki.

“There are some amazing things happening right here on our island,” Kimura says. “It’s great to see children’s eyes light up when they experience something new.”